I’ve been at a day job for two mornings, teaching a workshop about contemporary adaptations to MA Theatre Practice students at Central School. Who knew that they have studios at Bankside?

It required me to go back through the Daughters of the Sun process, which was done quite instinctively & with very loose associations, and thinking about what choices were made at which point.

The fun of playing classical - why does everyone get very serious & want to do proper acting when a text comes into the room?

Generating a question / questions pertaining to a bit of classical theatre text (in this instance, Hedda Gabler) - now known as your constitution.

Collecting material from the text - anything from the dialogue to the stage directions to the image on the front cover - that associates with your constitution.

Associating material from outside the text - ideas, memories, songs, clips from films, anything.

Ways of treating and defamiliarising found text.

Note on dramaturgy : the importance of letting the audience into the game of the show.

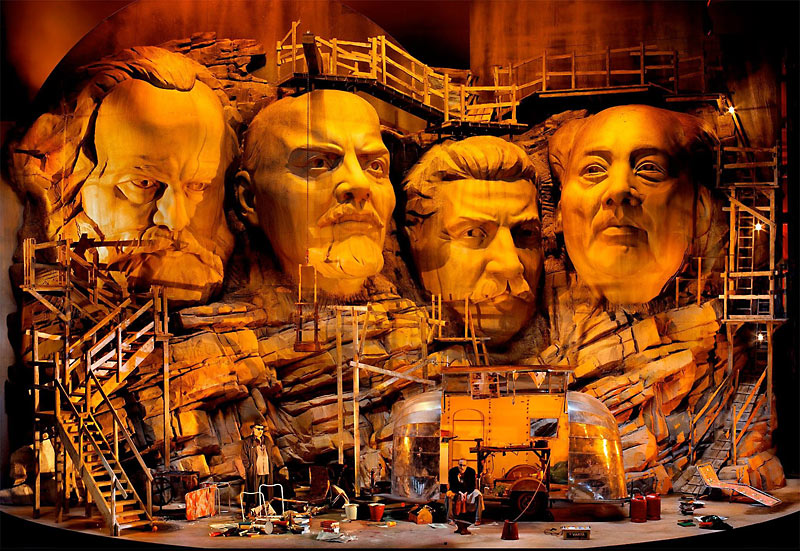

We talked about She She Pop, about Branden Jacob-Jenkins, about Ida Müller & Vegard VInge, about The Wooster Group, about Frank Castorf (briefly, but always), about Rashdash and about the Great Comet of 1812.

They have generated projects that they are working on all week and showing at the end of the week. I saw a couple of clips today - the earliest sketches of the earliest ideas - and there’s a Hedda Gabler/Joan Rivers mash-up in there. And one with Henrik Ibsen as a grumpy lounge piano player.

So there.